Jazz Counterpoint – Improvising Melody & Bass at the Piano

The full transcriptions and article can be found on (Patreon).

When musicians think about counterpoint, most likely they think about traditional fugues and “Bach” counterpoint. In some cases, they may also think about renaissance counterpoint, species writing and the music of Palestrina.

When you listen to improvising pianists like Brad Mehldau, Fred Hersch, and Egberto Gismonti, you will hear lots of interesting hand independence and a certain flair of counterpoint. You also hear how classical music influenced them in some way. Personally, it seemed logical to study the music of Bach and practice species exercises to improve my counterpoint and expand my improvisational abilities. So that’s what I did.

Eventually, I realized that species exercises and playing Bach don’t provide good frameworks for the kind of practice needed to improve improvisation. Sure, playing fugues and chorales may help inspire hand independence and counterpoint while improvising. You may even take this a step further, breaking down and arranging a jazz standard in two or four voices, in a chorale-like fashion. But these are very macro, high-level approaches to the problem of how to improvise more contrapuntally. I believe they need to be complemented with micro, note-to-note, repetitive practice with a foundation in physical gestures and relationships at the piano.

So below is my attempt to integrate the idea of “counterpoint” with physical relationships in an improvisatory practice. There are countless was to approach this, so I chose a style that is very relevant to playing jazz piano: improvising melodies & bass lines.

I’ve divided the article into these sections:

–

- Transcription Analysis (1700 words)

- Problem Solving – Integrating Bass Lines with Physical Relationships (1200 words)

- Examples of Bass Lines Over ii-V-I (600 words)

- Adding Right Hand, Simple Exercises (1100 words)

- Adding Right Hand, Advanced Exercises (1200 words)

- Meter, Rhythm and Time Feel (2000 words)

- New Directions: Extremely Advanced Exercises (2500 words)

–

There’s lots of information in this article, admittedly, probably too much. That’s because this article is more than just a collection of exercises. It’s a framework for practice. My hope is to help other pianists design their own exercises and structure their own practice, no matter the style. To achieve this, I believe it’s necessary to reflect as thoroughly as possible on everything from how to practice, improvisational hierarchies, cultivating active/passive relationships, and integrating the idea of a note with actual movement. That being said, if you’re a pianist simply looking for some exercises, you might want to skip to Examples of Bass Lines, Over ii-V-I.

Lastly, apologies for all my spelling and grammar mistakes. Feedback is welcome and thanks for reading!

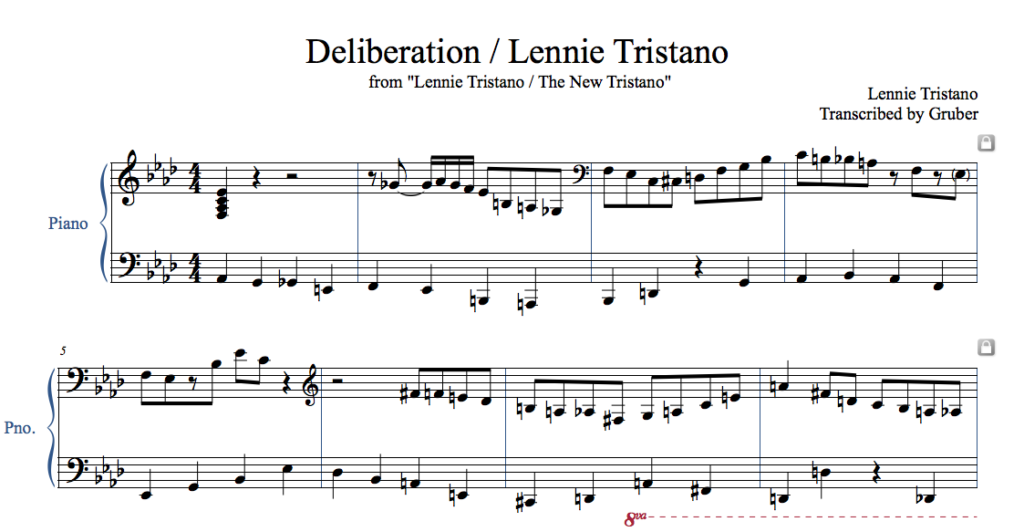

Article also includes transcriptions of Dave McKenna on Yardbird Suite and Lennie Tristano on Deliberation. These PDFs are only the first two pages. The full transcriptions and article can be found on (Patreon).

Transcription Analysis

To start, I’ve completed transcriptions of Dave McKenna on Yardbird Suite and Lennie Tristano on Deliberation. PDFs Attached! The McKenna is difficult to find online, so I’ve also attached a Mp3.

There are many ways we could analyze these transcriptions. A more traditional method would involve harmonic/functional analysis – every note is labeled in relation to a chord and chord progression. From this we can derive scales, licks, riffs, patterns, and other vocabulary to use in our own improvisations. With this method, the first four bars of the McKenna solo (measure 33) might look like this:

This kind of analysis is very helpful and can be used for the benefit of musicians who play different instruments. One problem though, is that harmonic relationships are derived in part, if not primarily, from physical relationships. A more complete analysis then, should include a proposed mapping of the physical gestures used to play this music at the piano:

This is similar to the approach I took with my transcription and “deep analysis” of Sugar Ray by Phineas Newborn Jr. Because playing the piano can also include a visual dimension, physical gestures can be connected to visual patterns of white and black notes at the piano.

I don’t intend to analyze these transcriptions like this. For one, it’s extremely time consuming. Analyzing and producing images of these four bars took me 4 hours! Secondly, my goal of transcribing and analyzing isn’t to simply learn about the notes and physical gestures of a single performance. It’s to learn more broadly about McKenna and Tristano as pianists, and about how to improvise and play jazz piano. Unfortunately, all of these methods described above neglect the improvisational nature of the performances. Studying improvised music requires a whole new analytical toolkit that includes analyzing complex improvisational hierarchies and probabilities.

As my brother once said: “There are eleventy billion ways of quantifying randomness, most of them requiring graduate degrees in math or statistics to understand.”

I don’t pretend to understand the cognitive processes involved in improvisation, or the mathematical tools that can be used to analyze them. But I’ve transcribed a lot of improvised piano music, and have made many observations that have helped me improve my practice. Though elementary by comparison to experts in statistics, using terms like “hierarchies” and “probabilities” gives me a framework for understanding improvised performance, creating exercises, and practicing. Though it will be far from a comprehensive analysis, I’d like to highlight some of these observations that have helped inform my practice. I tread softly and humbly!

Side Note: I’m currently reading “Music and Probability” by David Temperley. Some of my terminology is from what I learned in this book.

—

This style of counterpoint, as featured in the Mckenna and Tristano solos, is a good place to start understanding some of these hierarchal features in improvised performances. Noticing repetitive structures can be a helpful first step. Sometimes these are explicitly clear, other times they’re vague and taken for granted. Sometimes there are structures within structures.

For example, in Deliberation, Tristano is repetitively playing:

- quarter note “bass lines” in the left hand

- eighth note, eight note triplets, and sixteenth note “melodies” in the right hand

- in 4/4 meter

- at 143 bpm

- Eighth note melodies “behind the beat.”

- over a 32 bar harmonic cycles (Indiana in Ab)

- Bb7 arpeggios in 3-4 & 13-14 in this harmonic cycle (left hand)

- Right hand melodic pivots/direction changes on two black notes – measures 2, 16, 17, 18, (23), 26, 33, 38, 42, 47, 48, 54, 63, 66, 67, 82 (86), 94, 97, 98, 111, 125, 131, 133, (136), 140, 144.

- Chromatic reharmonizations in both hands simultaneously

- Between the notes G2 and F6 in the right hand

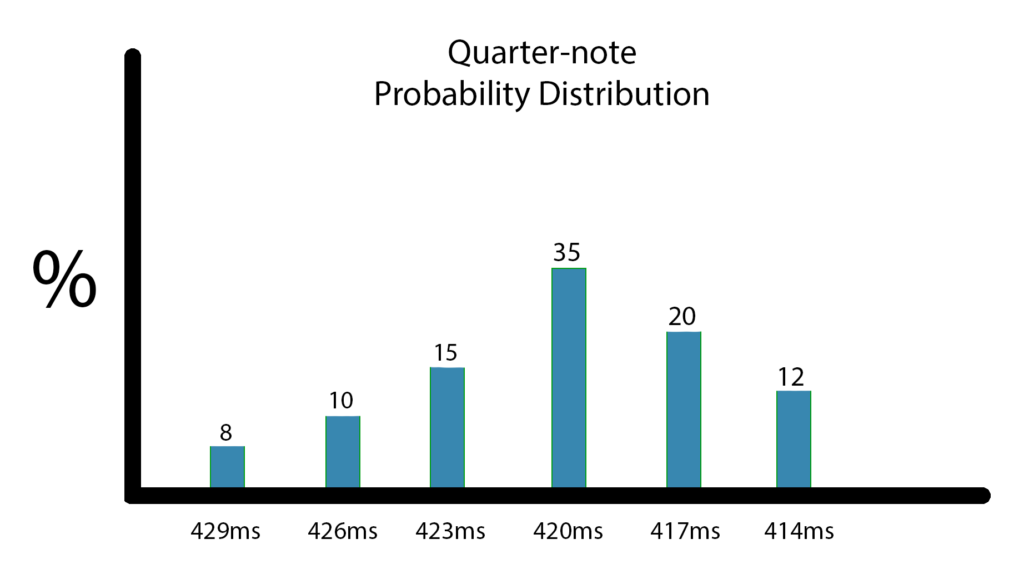

These are surface observations, made with many assumptions about certain structures. For example, Tristano isn’t really playing at 143 bpm. If you measured it more precisely, every quarter note in the left-hand would probably be fluctuating between 140 and 145 bpm. A more precise way to analyze this would be to create some kind of probability distribution. What is the probability of Tristano playing the next left-hand quarter note exactly 420 milliseconds after the previous one (143 bpm)?

Certainly not 100%. But what is the probability of Tristano playing the next left-hand quarter note 414-429 milliseconds (140-145bpm) after the previous one? This would be closer to 100%. Using mostly round numbers, a probability distribution could look something like this:

Considering the chart above, if it existed, we may look at all of the values and determine that Tristano is mostly performing at 143 bpm. In this case, “143 bpm” is being used as a practical abstraction of what is actuallybeing playing (Even using “143 bpm” is a bit bizarre – we would more likely use 140 or 145 bpm).

It’s important to ‘understand our understandings’ of these kinds of practical abstractions. To say Tristano is performing at 145bpm is both correct and incorrect, depending on what you’re referring to. If used to simplify some kind of probability distribution, then the analysis is more complete and correct compared to using it as a literal and objective measurement.

To make things more complicated, this doesn’t consider joint probabilities. Playing left-hand quarter notes at 143bpm isn’t independent from other aspects of the performance. A probability distribution that measures quarter notes could also consider the 4/4 meter. Tristano might be more likely to play downbeats 420 milliseconds after beat 4, than other parts of the measure. It’s also possible Tristano’s left-hand rushes or drags when the right hand is playing sixteenth notes, compared to when he’s playing eighth notes, or not at all.

Unfortunately, quantifying and calculating all the abstractions and joint probabilities is way beyond the scope of this article, and my expertise. I mention these things to acknowledge how immensely complex this type of analysis is, and that if we’re going to make any headway in improving our piano practice, using abstractions and making structural assumptions is necessary and inevitable. Analyzing improvised music through the lens of hierarchies and probabilities is extremely informative, but our analysis will have to remain on the surface, with observable repetitive structures.

—

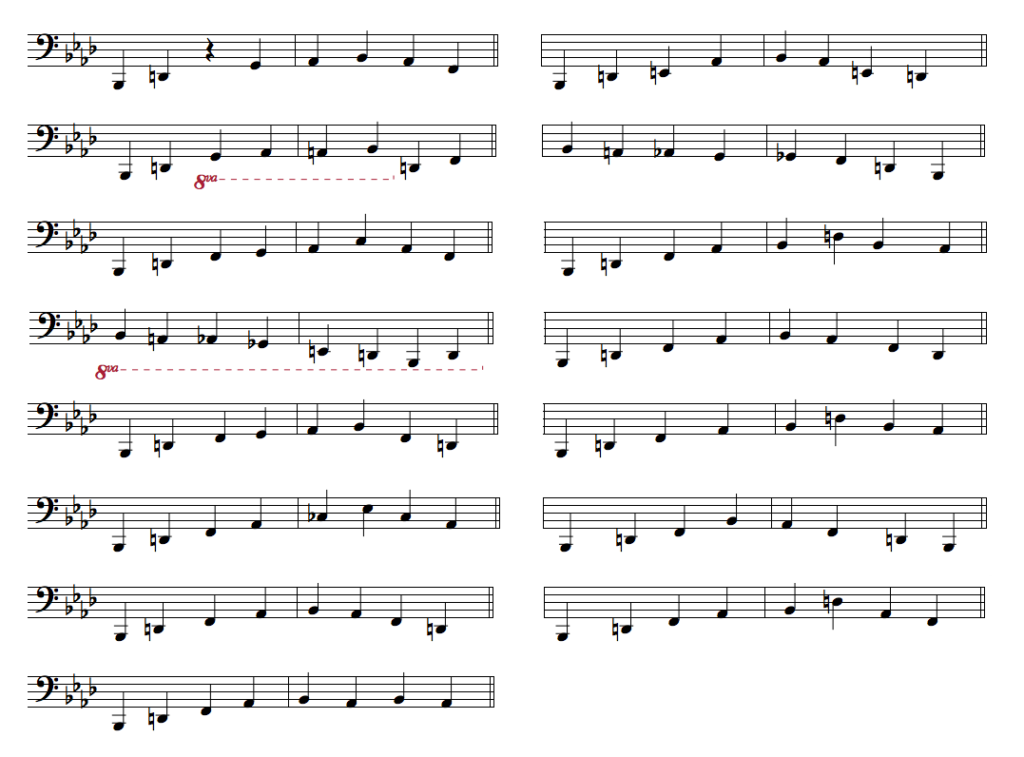

Looking at another example, I mentioned that Tristano is repetitively playing over Indiana, a 32-bar harmonic cycle in Ab major. In measures 3-4, 13-14, and 19-20 of this form, it’s common to play Bb7 (V of V). Tristano plays through the form five times, meaning these two measures of Bb7 occurs 15 times. Here is every one of his left hand bass lines in these two measures:

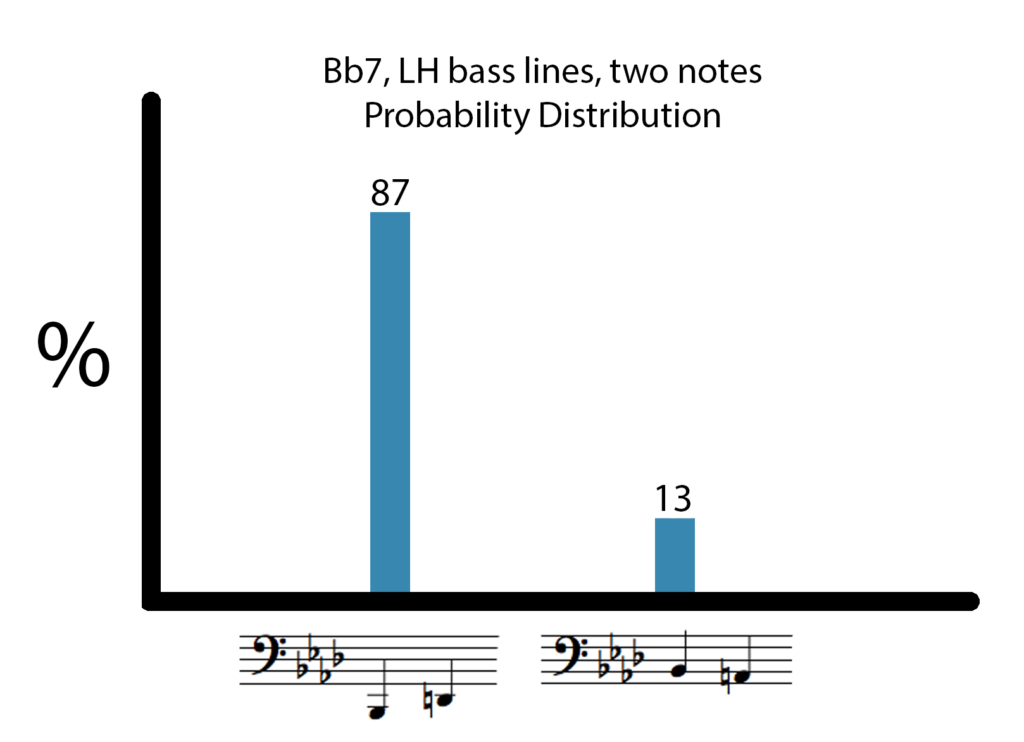

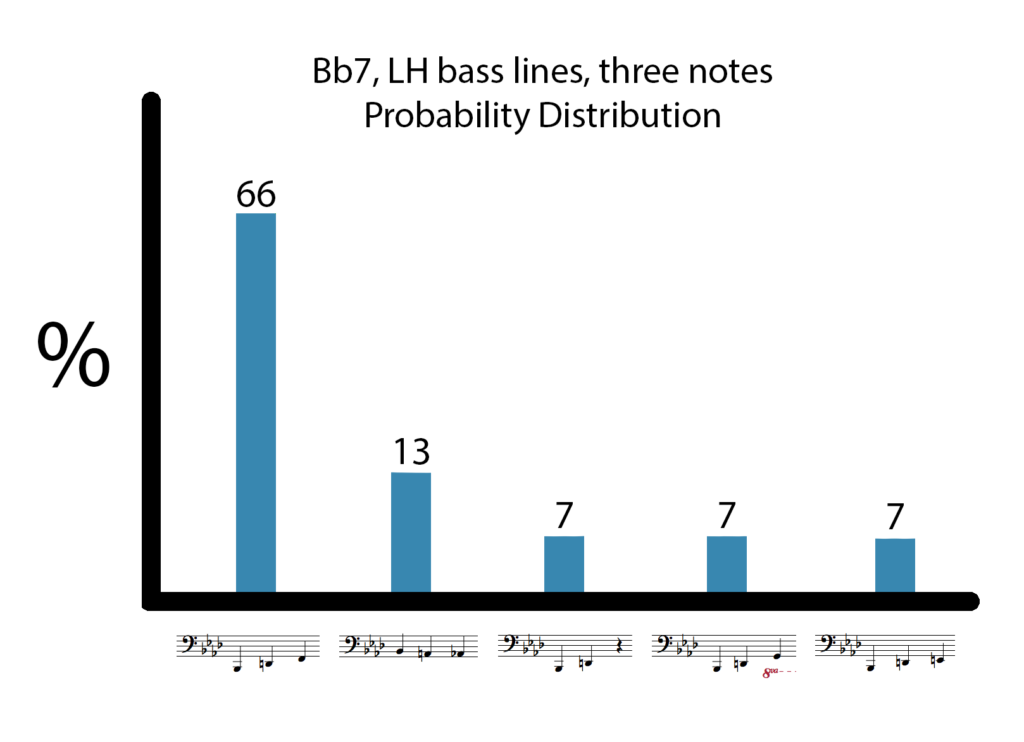

They’re all different. But they’re also very similar. The repetitive structure extends deeper than just playing Bb7 in measures 3-4, 13-14, and 19-20. Depending on how you abstract, you could argue that there are really only two variations – ascending to D, and descending to A from Bb. Also, considering probabilities, these two variations are hardly equal:

With only two weighted possibilities, from this perspective, the left hand is mostly compositional. Considering a third note adds more complexity, but still with an observable, hierarchal composition:

Why is there such minimal variation? There are countless ways to play a bass line over Bb7, but clearly Tristano considers certain spatial and directional relationships more desirable than others. I would argue that this composition is a result of both conscious harmonic patterns, but also conscious and economical physical gestures. Ascending to D and F is a logical harmonic choice, considering the rules of harmony and playing bass lines. With the 5th, 4th or 3rd finger on Bb in the left hand, it’s also a logical and economical ‘physical’ choice to directionally move 5-4-3, 5-3-2, 4-3-2, 4-2-1 or 3-2-1. In this case, such minimal variation, as shown in the probability distribution above, could be connected to Tristano often playing Bb with his 5th, 4th or 3rdfinger.

Of course, we’ll never know how Tristano actually played this. It’s possible that he always plays Bb with his thumb. I would argue that ascending to D and F from the thumb is less economical, but (especially at a slower tempos) still possible……. just less likely.

—

If we are to learn anything from this, it’s that fingering is consequential. The finger a pianist uses to play a note helps determine the probabilities of certain pathways being explored. When we practice bass lines at the piano, the composition of notes should be integrated with the composition of fingerings and hand positions (more on this later).

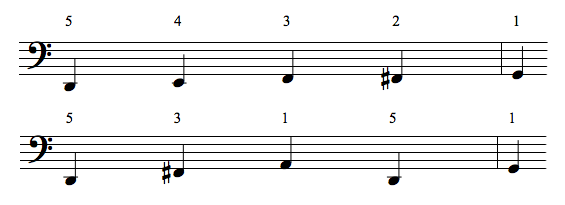

We can also learn about the degree in which pianists “improvise” left hand bass lines. Taking a look at the Mckenna transcription, his bass lines generally have less variation than Tristano’s. For example, starting from his improvisation in measure 33, he plays II7-V7-Imaj7 in C major nine times:

If we knew how Mckenna physically played this, this minimal variation would probably also be reflected in his fingerings and hand positions. The root of G7 is approached from below, and the chord is arpeggiated downward every time. The downbeat is likely being played with the thumb, and the G an octave below is likely being played with the 5th finger, every time.

D7 has a little more melodic and physical variation, but not much. The simplest melodic/physical connection would be to associate each variation with its own fingering, 5-4-3-2-1 and 5-3-1-5-1.

The problem with this is that it assumes a descending approach to the root of D7. If approached from above, from Eb, E, or A, then these two fingering variations are likely.

If approaching from below however, playing D with the 5th finger is unlikely. Playing these two bass lines efficiently and economically would require some adaptive fingering.

Considering this, we can learn a couple of things. For one, “improvising” bass lines with minimal variation is common practice. This is helpful because as we get into practicing bass line patterns, starting with minimal variation is more efficient and manageable anyways. Secondly, minimal variation can be reflected in both a sequence of notes and the fingerings/hand positions for playing them. Exercises that include simple, adaptive fingerings can lay the foundation for exploring this kind of counterpoint in an improvisatory practice.

Designing a Practice Strategy

We’ve learned a few things from my observations above. Most importantly, Tristano and McKenna aren’t fully “improvising” their LH bass lines. It would be more accurate to say they’re playing from “weighted possibilities.” The distinction is significant. It moves us away from treating improvisation as an ideal and gives us permission to explore a spectrum of improvisation and composition.

It’s common practice and perfectly acceptable to perform bass lines with minimal variation, if not completely composed, as if a classical composition. When designing a practice strategy and routine, you might ask yourself: How important is it that your LH improvises the bass line? What degree of spontaneity is “acceptable?” If you’re not interested in spontaneity and improvisation, you can probably skip this section. Compose a bass line, learn it with good fingering, and focus on right-hand improvisation!

If you ARE interested in some degree of improvisation and spontaneity, starting with minimal variation is more efficient and manageable anyways, but we have a problem. There’s an overwhelming number of ways to play a bass line over say, ii-V-I in C Major. We need a place to start, and we need to be smart with how we filter the options. As a general goal, we want to practice the fewest number of bass lines that give us most flexibility and lays groundwork for freer improvisation. This work includes integrating the notes of a bass lines with the physical gestures needed to play them.

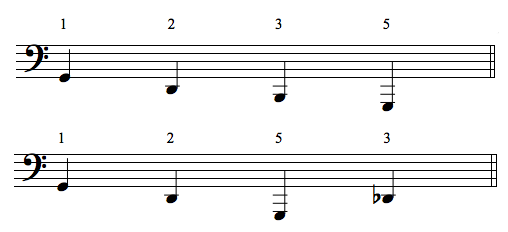

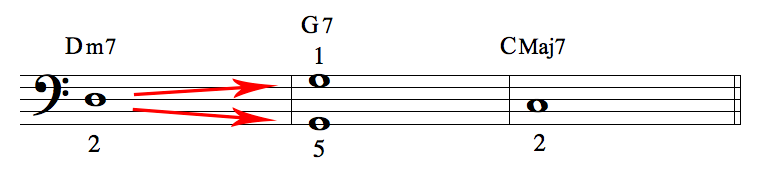

For example, let’s consider just the roots of ii-V-I in C Major. There are a few different ways we can order the roots. Here’s one:

Just as there are many different ways we can order the roots, there are many different ways we can play them. 5-1-5 might be your first solution, and it’s a good one:

The problem with starting on 5 though is that it limits your range of motion to ascending. There may be a situation where you would like to “improvise” your bass line and choose to descend to G. In this case, using the 2nd finger to play D keeps both options open.

This doesn’t mean we practice this starting only on the 2nd finger. There are going to be situations when we arrive at Dm7 on the 5th finger. After all, we don’t know what’s preceding Dm7. A7 perhaps? (more on this later). The point is to train our hands to be adaptive at a given time – to understand what pathways are available, and what pathways aren’t. With the 5th finger on D, it will be better to ascend. With the thumb on D, it will be better to descend. With the 2nd finger of D, different pathways are available at that moment.

When I say a pathway is ‘available,’ I mean it’s more economical compared to other pathways. Obviously, with the 5th finger on D, you could still descend, but this potentially causes conflict between what your brain wants to play and what your hands can play. The point of these articles is to integrate and encourage communication between brains and hands. It’s more comfortable and economical to ascend with the 5th finger on D, so we want to shape what we’re thinking and hearing to prefer that pathway. This means every note, every interval, and every quarter note is related to the fingers that play them. Ideally, we can’t think of the note ‘D’ without ALSO thinking about which finger plays it. As we write and practice bass lines, this is something we’ll be taking into consideration.

Now, what comes before Dm7?

Eventually, I’ll be writing a more detailed article about practicing. In the meantime, I think it’s important I touch on a few things here. The first is about the relationship between difficulty and loop cycles.

When practicing, we create repetitive structures that contain certain elements that we want to improve. It’s important to remember that we have full control over the length of these repetitive structures. There’s a tendency in jazz to practice over the form of a tune. This is good because what we’re practicing has context. The problem with this is that practicing longer cycles (like a 32-bar jazz tune) is more difficult than shorter cycles (like a two-bar loop). By the time you reach bar 32, and have played though all the tune’s chords and harmonic modulations, you’ve forgotten all the mistakes you made in bar 1. So, you’ll probably repeat them again. This isn’t good practice.

As a general rule, if something is too difficult we won’t learn and improve. Same for when it’s too easy. When practicing then, you always want to be in the difficulty “sweet spot.” Not too hard, not too easy. If you’re practicing at the right difficulty level, you WILL see improvement, within a few minutes in fact.

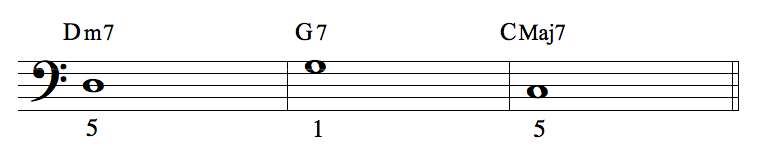

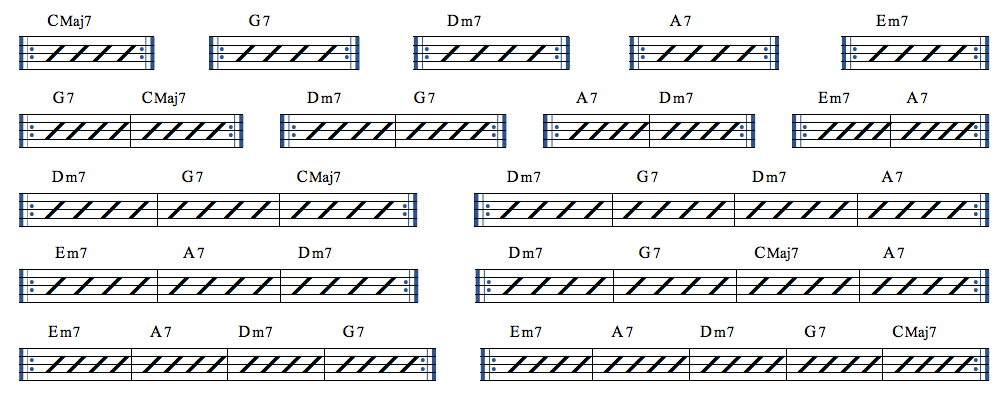

Breaking down the form of the tune into smaller parts is a way to manage difficulty. Instead of looping the 32-bar form, we can loop the first four bars, or the first two bars of a tune. From this, we’re isolating the tune’s building blocks, and we can assemble them at a pace that matches our most appropriate difficulty level. This is necessary for isolating the relationships we’re trying to improve, but takes our practice slightly out of context. After all, sometimes harmonic building blocks only make sense in relation to other building blocks. If we create a repetitive cycle that loops Dm7-G7-CMaj7, what comes before Dm7? Based on the tune, we might adjust the cycle to A7-Dm7-G7-CMaj7. But now, what comes before A7? Our new cycle could be Em7-A7-Dm7-G7-CMaj7, but now our cycle is getting longer and we’re back to the original problem of practicing over cycles that are too long and difficult.

My solution over the last year, was to be extremely granular with how I piece together harmonic building blocks. If the tune I’m working on contains Em7-A7-Dm7-G7-CMaj7, here are some of the cycles I would have isolated:

It doesn’t matter what order these building blocks are pieced together. What matters is how piecing these together increases or decreases difficulty. Eventually, you’ll be ready to assemble all the building blocks to form the full-length tune.

This process of breaking down, assembling, expanding, and diminishing harmonic building blocks is one of many “knobs” at our disposal for managing difficulty. This idea of turning “knobs” to tweak exercises and manage difficulty is an analogy I use often. This particular knob isolates broad harmonic relationships. We still need to fill these building blocks with notes and exercises. More knobs are coming!

A few more thoughts on practicing:

If your practicing doesn’t have unbearably tedious repetition, you’re probably not doing right. By tedious repetition, I mean note-to-note, finger-to-finger, precise, and deliberate repetition – the kind of practice we like to avoid, but also the kind of practice that’s necessary for improvement. This is not a creative activity. Even though we might be practicing to improve spontaneity, this kind of practice has extremely little, if not, zero improvisation.

That being said, you’re probably not doing it right if your practicing ONLY has unbearably tedious repetition. A musician’s practice, broadly speaking, also includes elements of play. This could include relaxing the rules that direct tedious repetition, improvising freely without rules, or jamming with friends.

I don’t mean to suggest that practicing should only have tedious repetition. In my experience as a teacher though, this is generally what’s missing from student’s day-to-day practice routines. We’re good at playing, not so good at practicing. This is understandable because cultivating this kind of routine is difficult to manage in an improvisatory practice. It’s also more motivating to “play” than “practice.” But a balance needs to be struck. These articles are my attempt to help structure and encourage the repetitive side of practice routines.

Maybe, as a general guide, every 15mins of tedious repetitive practice could be matched with 15mins of play time. Every rule that’s strictly followed for 15mins can be broken for the next 15mins. You can try setting your own practice/play intervals. The tendency is always to move away from the repetitive grind, but the more you can keep coming back to it, the more improvement you’ll see!

Again, the topic of practicing deserves a whole article of its own, but for now, hopefully these three things will help guide you for now:

- Integrating notes with physical gestures when designing exercises

- Controlling repetitive cycles as a means to manage difficulty

- Finding a balance between playing and practicing

The next section expands on this idea of integrating notes with physical gestures.